Arctic summit in Moscow hears rival claims

Russia made its ambitions clear by planting a flag beneath the North Pole. An international meeting to try to prevent the Arctic becoming the next battleground over mineral wealth is taking place in Moscow. One quarter of the world's resources of oil and gas are believed to lie beneath the Arctic Ocean. Russia, Norway, Canada, Denmark and the United States have already laid claim to territory in the region.

Although the summit is promoting dialogue, a Kremlin adviser said Russia would defend its national interests.

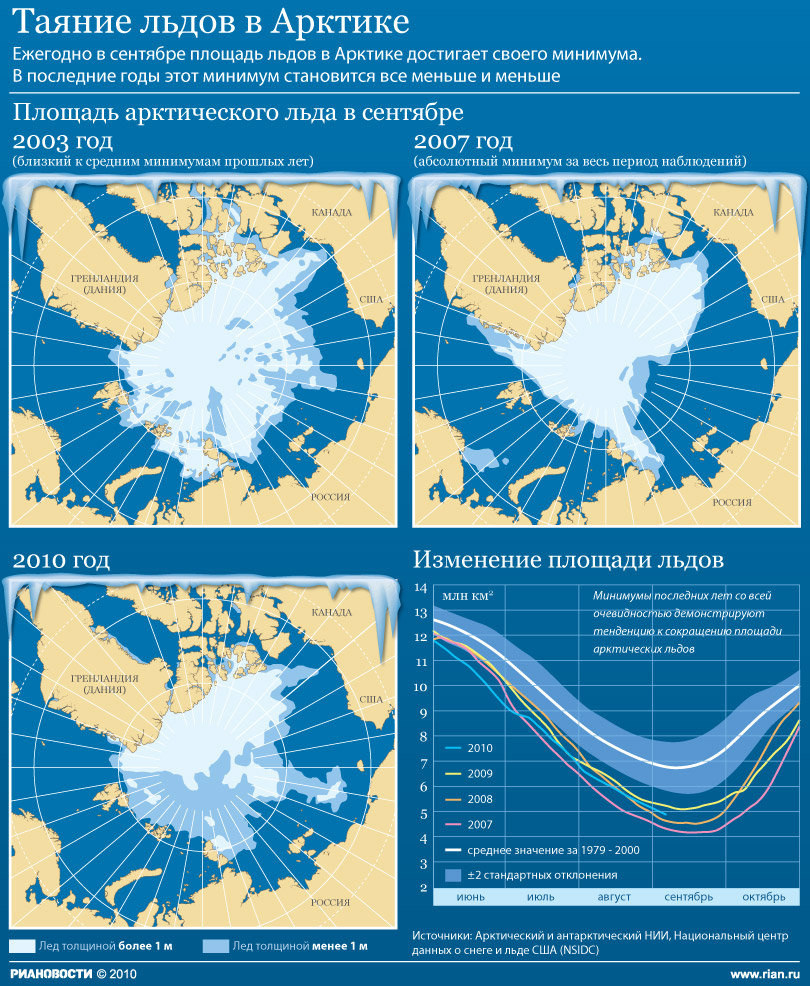

Senior Norwegian adviser Olaf Orpheum told the conference that nowhere else had seen "such dramatic changes in the surface of the Earth".

The race for the Arctic centres on an underwater mountain range known as the Lomonosov Ridge.

In 2001, Moscow submitted a territorial claim to the United Nations which was rejected because of lack of evidence.

Three years ago, a Russian expedition planted a titanium flag on the ocean floor beneath the North Pole in a symbolic gesture of Moscow's ambitions.

Law of the Sea

As evidence of the gathering momentum in the race for mineral resources, Russia has announced it will spend $64m (£40m; 48m euros) on research aimed at proving its case.

The man behind the 2007 polar expedition, Artur Chilingarov, has announced that he will attempt to launch a drifting research station next month.

Kremlin climate change adviser Alexander Bedritsky told reporters that Russia had a "strong chance" to win approval when it submitted its data to the UN in 2012-13.

Last week, Canada's foreign minister met his Russian counterpart in Moscow to discuss their competing claims.

Canada is likely to hand its file to the UN around 2013 and has said it is confident of its case.

Denmark plans to put forward its details by the end of 2014.

For the states involved in the territorial dispute, the key lies in obtaining scientific proof that the Lomonosov Ridge is an underwater extension of their continental shelf.

Under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, a coastal nation can claim exclusive economic rights to natural resources on or beneath the sea floor up to 200 nautical miles (370km) beyond their land territory.

But if the continental shelf extends beyond that distance, the country must provide evidence to a UN commission which will then make recommendations about establishing an outer limit.

Last week, Russia signed a treaty with Norway, ending a 40-year dispute over their maritime borders in the Barents Sea and Arctic Ocean.

Russian Arctic expert Lev Voronkov said the experience of the Cold War proved the need to work together.

"No one problem of contemporary Arctic can be resolved by one country alone. So that's why I think that we are doomed to co-operate in the Arctic. And military confrontation especially is completely counterproductive."

Russian President Dmitry Medvedev said last week that Nato's presence in the Arctic could raise additional problems.